In the early days of the World Wide Web – with the Year 2000 and the threat of a global collapse of society were still years away – the crafting of a website on the WWW was both special and increasingly more common. Courtesy of free hosting services popping up left and right in a landscape still mercifully devoid of today’s ‘social media’, the WWW’s democratizing influence allowed anyone to try their hands at web design. With varying results, as those of us who ventured into the Geocities wilds can attest to.

Back then we naturally had web standards, courtesy of the W3C, though Microsoft, Netscape, etc. tried to upstage each other with varying implementation levels (e.g. no iframes in Netscape 4.7) and various proprietary HTML and CSS tags. Most people were on dial-up or equivalently anemic internet connections, so designing a website could be a painful lesson in optimization and targeting the lowest common denominator.

This was also the era of graceful degradation, where us web designers had it hammered into our skulls that using and navigating a website should be possible even in a text-only browser like Lynx, w3m or antique browsers like IE 3.x. Fast-forward a few decades and today the inverse is true, where it is your responsibility as a website visitor to have the latest browser and fastest internet connection, or you may even be denied access.

What exactly happened to flip everything upside-down, and is this truly the WWW that we want?

User Vs Shinies

Back in the late 90s, early 2000s, a miserable WWW experience for the average user involved graphics-heavy websites that took literal minutes to load on a 56k dial-up connection. Add to this the occasional website owner who figured that using Flash or Java applets for part of, or an entire website was a brilliant idea, and had you sit through ten minutes (or more) of a loading sequence before being able to view anything.

Another contentious issue was that of the back- and forward buttons in the browser as the standard way to navigate. Using Flash or Java broke this, as did HTML framesets (and iframes), which not only made navigating websites a pain, but also made sharing links to a specific resource on a website impossible without serious hacks like offering special deep links and reloading that page within the frameset.

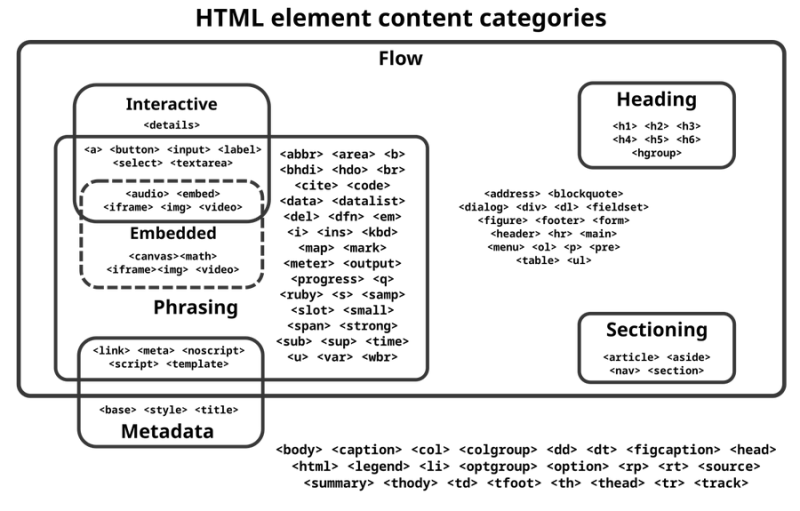

As much as web designers and developers felt the lure of New Shiny Tech to make a website pop, ultimately accessibility had to be key. Accessibility, through graceful degradation, meant that you could design a very shiny website using the latest CSS layout tricks (ditching table-based layouts for better or worse), but if a stylesheet or some Java- or VBScript stuff didn’t load, the user would still be able to read and navigate, at most in a HTML 1.x-like fashion. When you consider that HTML is literally just a document markup language, this makes a lot of sense.

Credit: Babbage, Wikimedia.

More succinctly put, you distinguish between the core functionality (text, images, navigation) and the cosmetics. When you think of a website from the perspective of a text-only browser or assistive technology like screen readers, the difference should be quite obvious. The HTML tags mark up the content of the document, letting the document viewer know whether something is a heading, a paragraph, and where an image or other content should be referenced (or embedded).

If the viewer does not support stylesheets, or only an older version (e.g. CSS 2.1 and not 3.x), this should not affect being able to read text, view images and do things like listen to embedded audio clips on the page. Of course, this basic concept is what is effectively broken now.

It’s An App Now

Somewhere along the way, the idea of a website being an (interactive) document seems to have been dropped in favor of a the website instead being a ‘web application’, or web app for short. This is reflected in the countless JavaScript, ColdFusion, PHP, Ruby, Java and other frameworks for server and client side functionality. Rather than a document, a ‘web page’ is now the UI of the application, not unlike a graphical terminal. Even the WordPress editor in which this article was written is in effect just a web app that is in constant communication with the remote WordPress server.

Somewhere along the way, the idea of a website being an (interactive) document seems to have been dropped in favor of a the website instead being a ‘web application’, or web app for short. This is reflected in the countless JavaScript, ColdFusion, PHP, Ruby, Java and other frameworks for server and client side functionality. Rather than a document, a ‘web page’ is now the UI of the application, not unlike a graphical terminal. Even the WordPress editor in which this article was written is in effect just a web app that is in constant communication with the remote WordPress server.This in itself is not a problem, as being able to do partial page refreshes rather than full on page reloads can save a lot of bandwidth and copious amounts of sanity with preserving page position and lack of flickering. What is however a problem is how there’s no real graceful degradation amidst all of this any more, mostly due to hard requirements for often bleeding edge features by these frameworks, especially in terms of JavaScript and CSS.

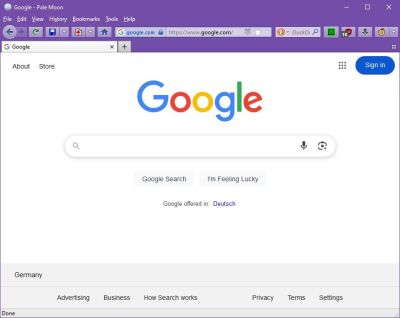

Sometimes these requirements are apparently merely a way to not do any testing on older or alternative browsers, with ‘forum’ software Discourse (not to be confused with Disqus) being a shining example here. It insists that you must have the ‘latest, stable release’ of either Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox or Apple Safari. Purportedly this is so that the client-side JavaScript (Ember.js) framework is happy, but as e.g. Pale Moon users have found out, the problem is with a piece of JS that merely detects the browser, not the features. Blocking the

browser-detect-* script in e.g. an adblocker restores full functionality to Discourse-afflicted pages.Wrong Focus

It’s quite the understatement to say that over the past decades, websites have changed. For us greybeards who were around to admire the nascent WWW, things seemed to move at a more gradual pace back then. Multimedia wasn’t everywhere yet, and there was no Google et al. pushing its own agenda along with Digital Restrictions Management (DRM) onto us internet users via the W3C, which resulted in the EFF resigning in protest.

Google Search open in the Pale Moon browser.

Although Google et al. ostensibly profess to have only our best interests at heart when features were added to Chrome, the very capable plugins system from Netscape and Internet Explorer taken out back and WebExtensions Manifest V3 introduced (with the EFF absolutely venomous about the latter), privacy concerns are mounting amidst concerns that corporations now control the WWW, with even new HTML, CSS and JS features being pushed by Google solely for its use in Chrome.

For those of us who still use traditional browsers like Pale Moon (forked from Firefox in 2009), it is especially the dizzying pace of new ‘features’ that discourages us from using effectively non-Chromium-based browsers, with websites all too often having only been tested in Chrome. Functionality in Safari, Pale Moon, etc. often is more a matter of luck as the assumption is made by today’s crop of web devs that everyone uses the latest and greatest Chrome browser version. This ensures that using non-Chromium browsers is fraught with functionally defective websites, as the ‘Web Compatibility Support’ section of the Pale Moon forum illustrates.

Question is whether this is the web which we, the users, want to see.

Low-Fidelity Feature

Another unpleasant side-effect of web apps is that they force an increasing amount of JS code to be downloaded, compiled and ran. This contrasts with plain HTML and CSS pages that tend to be mere kilobytes in size in addition to any images. Back in The Olden Days

In this and earlier described scenarios the consequence is the same: you must be using the latest Chromium-based browser to use many sites, you will be using a lot of RAM and CPU for even basic pages, and forget about using retro- or alternative systems that do not support the latest encryption standards and certificates.

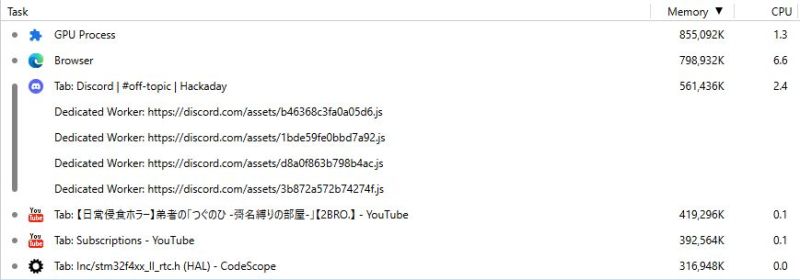

The latter is due to the removal of non-encrypted HTTP from many browsers, because for some reason downloading public information from HTTP and FTP sites without encrypting said public data is a massive security threat now, and the former is due to the frankly absurd amounts of JS, with the Task Manager feature in many browsers showing the resource usage per tab, e.g.:

The Task Manager in Microsoft Edge showing a few active tabs and their resource usage.

Of these tabs, there is no way to reduce their resource usage, no ‘graceful degradation’ or low-fidelity mode, so that older systems as well as the average smart phone or tablet will struggle or simply keel over to keep up with the demands of the modern WWW, with even a basic page using more RAM than the average PC had installed by the late 90s.

Meanwhile the problems that we web devs were moaning about around 2000 such as an easy way to center content with CSS got ignored, while some enterprising developers have done the hard work of solving the graceful degradation problem themselves. A good example of this is the FrogFind! search engine, which strips down DuckDuckGo search results even further, before passing any URLs you click through a PHP port of Mozilla’s Readability. This strips out anything but the main content, allowing modern website content to be viewed on systems with browsers that were current in the very early 1990s.

In short, graceful degradation is mostly an issue of wanting to, rather than it being some kind of unsurmountable obstacle. It requires learning the same lessons as the folk back in the Flash and Java applet days had to: namely that your visitors don’t care how shiny your website, or how much you love the convoluted architecture and technologies behind it. At the end of the day your visitors Just Want Things to Work

Tl;dr: content is for your visitors, the eyecandy is for you and your shareholders.