A friend of mine is producing a series of HOWTO videos for an open source project, and discovered that he needed a better microphone than the one built into his laptop. Upon searching, he was faced with a bewildering array of peripherals aimed at would-be podcasters, influencers, and content creators, many of which appeared to be well-packaged versions of very cheap genericised items such as you can find on AliExpress.

If an experienced electronic engineer finds himself baffled when buying a microphone, what chance does a less-informed member of the public have! It’s time to shed some light on the matter, and to move for the first time in this series from the playback into the recording half of the audio world. Let’s consider the microphone.

Background, History, and Principles

A microphone is simply a device for converting the pressure variations in the air created by sounds, into electrical impulses that can be recorded. They will always be accompanied by some kind of signal conditioning preamplifier, but in this instance we’re considering the physical microphone itself. There are a variety of different types of microphone in use, and after a short look at microphone history and a discussion of what makes a good microphone, we’ll consider a few of them in detail.

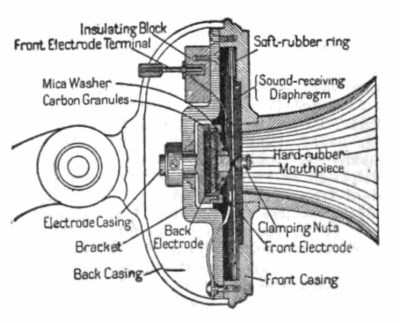

This one is from 1916, but you might have been using a carbon microphone on your telephone surprisingly recently.

The development of the microphone in the late 19th century is intimately associated with that of the telephone rather than the phonograph, as these recording devices were mechanical only and had no electrical component. The first practical microphones for the telephone were carbon microphones, a container of carbon granules mechanically coupled to a metal diaphragm, which formed a crude variable resistor modified by the sound waves. They were especially suitable for the standing DC current of a telephone line and though they are too noisy for good quality audio they continued in use for telephones into recent decades. The ancestors of the microphones we use today would arrive in the early years of the 20th century along with the development of electronic amplification and recording.

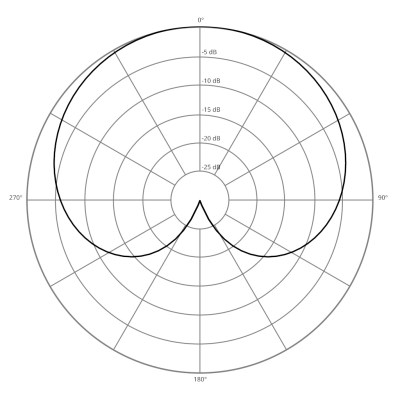

The polar pattern of a cardioid microphone. Nicoguaro, CC BY 4.0.

The job of a microphone is to take the sounds surrounding it and convert them into electrical signals, and invariably that starts with some form of lightweight diaphragm which vibrates in response to the air around it. The idea is that the mass of the diaphragm is as low as possible such that its physical properties have a minimal effect on the quality of the audio it captures. This diaphragm will be surrounded by whatever supporting structure it needs as well as any other components such as magnets, and the structure surrounding it will be designed to minimise vibration and shape the polar pattern over which it is sensitive.

Depending on the application there are microphone designs with a variety of patterns, from an omnidirectional when recording a room, through bidirectional figure-of-eight used in some studio environments, to cardioid microphones for vocals and speech with a kidney-shaped pattern, to extremely directional microphones used by filmmakers. Of those the cardioid pattern is the one most likely to find itself in everyday use by someone like my friend recording voice-overs for video.

Having some idea of microphone history and principles, it’s time to look at some real microphones. We’re not going to cover every single type of microphone, instead we’re going to cover the three most common, to represent the ones you are likely to find for affordable prices. These are dynamic microphones, condenser microphones, and their electret cousins.

Dynamic Microphones

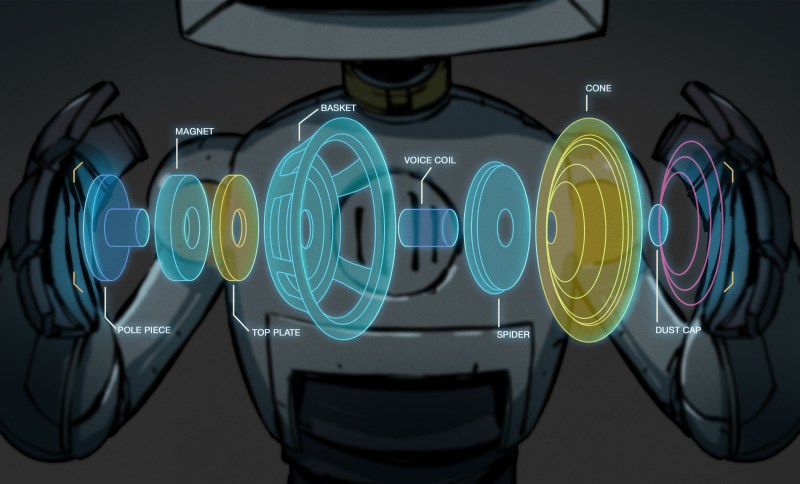

A dynamic microphone cartridge.

A dynamic microphone takes a coil of wire and suspends it from a diaphragm in a magnetic field. The diaphragm moves the coil, and thus an audio voltage is generated. The diaphragm will typically be a polymer such as Mylar, and it will usually be suspended around its edge by a folded section in a similar manner to what you may have seen on the edge of a loudspeaker cone. The output impedance depends upon the winding of the coil, but is typically in the range of a few hundred ohms. They have a low level output in the region of millivolts, and thus it is normal for them to connect to some kind of preamplifier which may be built in to a mixing desk or similar. The microphone cartridge pictured is from a cheap plastic bodied one bundled with a sound card. You can see the clear plastic diaphragm, as well as the coil. The magnet is the shiny metal object in the centre.

Capacitor Microphones

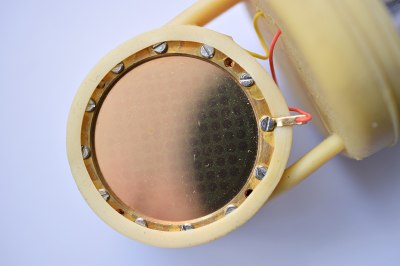

The diaphragm of a capacitor microphone cartridge. ElooKoN, CC BY-SA 4.0

A capacitor microphone is, as its name suggests, a capacitor in which one plate is formed by a diaphragm.This diaphragm is usually an extremely thin polymer, metalised on one side.

The sound vibrations vary the capacitance of the device, and this can be retrieved as a voltage by maintaining a constant charge across the microphone. This is typically achieved with a DC voltage in the order of a few hundred volts. Since the charge remains constant while the capacitance changes with the sound, the voltage on the microphone will change at the audio frequency. Capacitor microphones have a high impedance, and will always have an accompanying preamplifier and power supply circuit as a result.

Electret Microphones

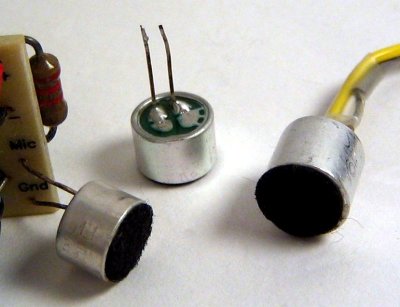

The ubiquitous cheap electret microphone capsules. Omegatron, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Electret microphones are a special class of capacitor microphone in which the charge comes from an electret material, one which holds a permanent electric charge. They thus forgo the high voltage power supply for their DC bias, and usually have a built-in FET preamp in the cartridge needing a low voltage supply such as a small battery. The attraction is that electret cartridges can be had for very little money indeed, and that the cheap electret cartridges are of surprisingly high quality for their price.

That’s All Very Well, But Which One Should I Buy?

So yes, even knowing a bit about microphones, you’re still left just as confused when browsing the options. The questions you need to ask yourself aside from your budget then are these: what do I want to use if for, and what do I want to plug it in to? Let’s talk practicalities.

You can’t go too far wrong with a Shure SM58 (Or a slightly inferior copy). Christopher Sessums CC BY-SA 2.0.

There are a variety of different physical form factors for microphones, usually at the cheaper end of the market a styling thing emulating famous more expensive models. Often the ones aimed at content creators have a built-in desk stand, however you may prefer the flexibility of your own stand. There are also all manner of pop filters and other accessories, some of which appear to be more for show than utility.

You will need to ask yourself what polar pattern you are looking for, and the answer is cardioid if you are recording your speech — its directional pattern rejects background noise, and focuses on what comes out of your mouth. You might also think about robustness; are you taking this microphone out on the road? A stage microphone makes a better choice if it will see a hard life, while a desktop microphone might make more sense if it rarely leaves your computer.

In front of me where this is being written is my microphone. I take it out on the road with me so I needed a robust device, plus I like the look of a traditional handheld microphone. The standard stage vocal dynamic microphones is unquestionably the Shure SM58, a robust and high-performance device that has stood the test of time. At £100, it’s out of my price range, so I have a cheaper mic from another well-known professional audio manufacturer that is obviously their take on the same formula. It is plugged in to a high-quality musician’s USB microphone interface, a USB sound card and mixer all-in-one. It serves me well, and if you’ve caught a Hackaday podcast with me on it you’ll have heard it in action.

If you’re not going to invest into an audio interface, you will be looking for something with a built-in amplifier and ADC, and probably something that plugs straight into USB. These are myriad, and the quality varies all over the place. For voice recording, a cardioid pattern makes sense, and an amplifier with low self-noise is desirable. If the amplifier picks up the USB bus noise, move on.

So in this piece I hope I’ve answered the questions of both my friend from earlier, and you the reader. It’s no primer for equipping a high-end studio, but if you’re doing that it’s likely you’ll already know a lot about microphones anyway.